Richard Millett QC, the lead counsel to the Grenfell Tower Inquiry, accused the construction industry of a “long run-up of incompetence” prior to the Grenfell Tower disaster.

And he said that companies involved in the refurbishment of the building, where a June 2017 blaze resulted in the death of 72 people, were still blaming each other.

In his closing statement to the Inquiry, Millett asserted that “every one of the deaths…was avoidable”.

He said the reasons were “many, complex and in many cases inextricably interlinked. Some had an immediately causative effect and others less so.”

He told the Inquiry: “It is open to you on the evidence to conclude that there was a long run-up of incompetence and poor practices in the construction industry and the fire engineering and architects’ profession; weak and incompetent building control; cynical and possibly even dishonest practices in the cladding and insulation materials manufacturing sector; incompetence, weakness and malpractice by those responsible for testing those materials; the failure of central government to act, despite known risks; failures of competence, training and oversight within the TMO, and over it by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea; a failure by the London Fire Brigade to learn the lessons of Lakanal, and other fires, and to train its operational staff to collect, understand and act on the risks presented by modern construction methods and materials.”

Millett also criticised the “complex, opaque and piecemeal legislation” that lay behind the situation and an “over-reliance” by law and policymakers on out-of-date statutory guidance.

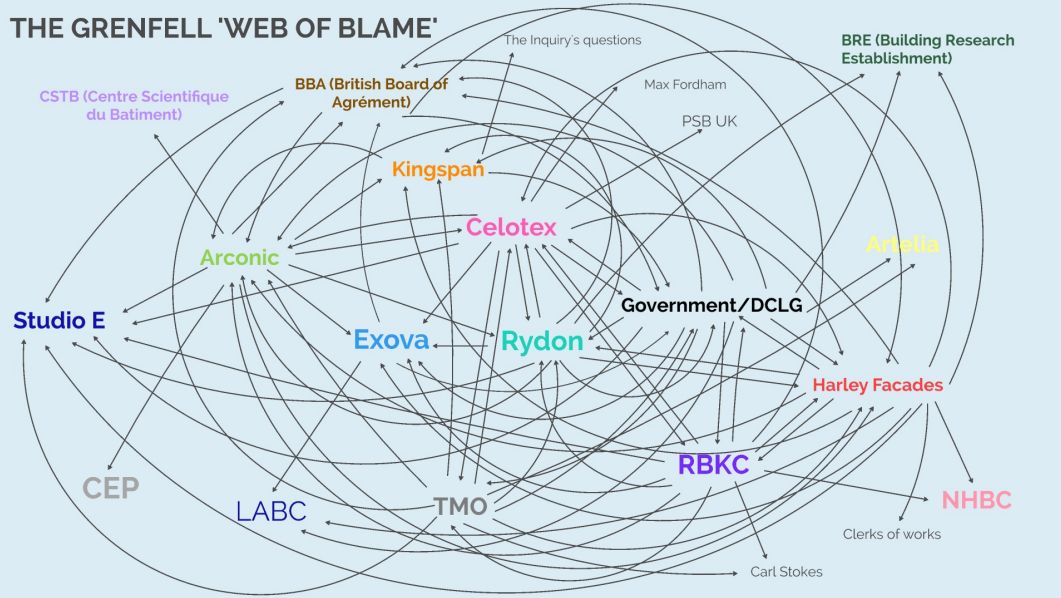

Web of blame

Millett said that the “merry-go-round of buck-passing" that he referred to at the opening of the Inquiry “turns still”. He said: “I had hoped that my task, and so your task in turn, would be made easier by candid admission of blame.”

He said: “Listening to the last three-and-a-half days of overarching closing statements from a range of core participants, if everything that has been said is correct, then nobody was to blame for the Grenfell Tower fire. Can that really be right?”

Millett produced a presentation to map out the “spider’s web of blame” (above). The diagrams set out the names of the companies and organisations involved in the refurbishment with arrows pointing to the organisations to which they have apportioned blame during the Inquiry, creating a dense web.

‘Maze of competing causes’

Millett said: “The reason to investigate the maze of parallel and competing causes is not only legal, but cultural. Many of the failings of many of the organisations revealed by the fire and the evidence about it are redolent of a culture pervasive through these organisations of dissociation, blame-shifting and defensiveness to cover up incompetence, lack of skill and experience, false and unverified assumptions, and plain carelessness or lack of engagement.

“There will have been many times in the evidence when I don’t doubt that you will have been struck by how many witnesses thought that something was somebody else’s job, but never bothered to check. And there is a moral dimension to this approach too. True regret is not the repeated and mournful use of the word ‘sorry’, but the achievement of a practical outcome reflecting permanent self-corrective action. The families of those who died and the wider public want to know who is to blame for this tragedy, how culpability is shared, and what will be done about it. Based on a close study and analysis of the facts, you can and you must help them answer that question. It is only then that the merry-go-round can stop and the families can start to get some kind of closure.”

Inquiry chair Sir Martin Moore-Bick and the panel will now decide who was to blame.

They are due to produce a report in 2023. Once the report has been published, the Met Police may begin criminal proceedings, but this is unlikely to happen before 2024.