If the industry could use all the health and safety information it collects in a more intelligent way, how would that change the role of the principal designer? A huge HSE-delivered programme could have the answers.

Wouldn’t it be handy if design software could flag up to its users when they were designing in a hazard? “Watch out, you’re creating an open edge there that could cause a fall from height. Have you considered these alternative solutions?” This is the intent behind a project called the Construction Risk Library. And while the project isn’t quite as advanced as the scenario above, it has proved the idea could work.

The project is part of a huge programme of work called Discovering Safety, delivered by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and funded by Lloyd’s Register Foundation. Initially running for five years with £10m of funding, the intention is that the programme will become self-sustaining.

The overarching aim of Discovering Safety is to find better ways to mine, manage and apply the vast amounts of data stored by both the HSE and companies in the construction sector. “Both Lloyd’s Register Foundation and the HSE are big advocates of making better use of data,” explains Steve Naylor, HSE technical lead for Discovering Safety. “We are sitting on huge data sets of intelligence here at the HSE.”

Construction blazes a trail

When Discovering Safety was first envisaged, there wasn’t a plan to focus on the construction industry. However, it soon became clear it would be a good place to start, says Naylor. “It became apparent early on that there was significant interest across construction,” he says. “With some of the big engineering projects generating huge amounts of data, they recognised the value of finding tools to make better use of that data. We realised that we could just focus on one sector and demonstrate what could be done.”

“One of the big shifts we want to see is towards designer-led risk management. We want the responsibility to shift to them, rather than designers seeing it as someone else’s role.”

It was important to get industry support and buy-in, says Naylor, both to identify how data could be deployed to improve construction’s safety performance, and so that projects would share their information too, for the wider good. There are several industry players listed as partners on the Discovering Safety programme, among them HS2, Atkins, AstraZeneca, Heathrow and the University of Manchester.

Though many of the current Discovering Safety projects are in the construction sector, there are some in other sectors. For instance, one is looking at ‘loss of containments’ – or spills – in the process industry, while another focuses on diving.

Many of the construction-focused projects will be transferable to other sectors. For instance, text mining: using machine learning to read text in documents and drawings. This is fundamental to many projects so was the first one to get under way. “It is very important because it underpins many of the other projects, but it has proved really challenging,” says Gordon Crick, HSE technical lead for Discovering Safety. “It has not bottomed out yet.”

In partnership with the National Centre for Text Mining at the University of Manchester (NaCTeM), HSE is working with 3,050 RIDDOR reports produced between 2011 and 2017 to train a tool to look for text. Sample documents were marked up manually using an annotation system devised by NaCTeM, with health and safety input from HSE, then used to train deep learning models.

The trained RIDDOR Text Analysis Tool allows users to input certain words and the tool will find them and display clusters of words around the one that was searched. Previously, RIDDORs could only be searched by searching predetermined fields.

Longer term, the goal would be to link searches up to safe working guidance that the HSE has produced or risks that have been identified on historic projects, so that someone working on a risk assessment could see what safe working advice is – as well as what has gone wrong in the past.

AI safety adviser

The Construction Risk Library is perhaps the most interesting of the Discovering Safety projects for Association of Project Safety (APS) members, who must surely see the same issues arising over and over again. It is aimed at designers in the preconstruction phase both to flag up potential risks and suggest ways to treat those risks.

“One of the big shifts we want to see is towards designer-led risk management,” says Crick. “We want the responsibility to shift to them, rather than designers seeing it as someone else’s role.”

One of the barriers to achieving this shift is the competency of designers. “We have to be concerned about the level of health and safety knowledge among some designers,” says Crick. Part of that knowledge gap is due to a lack of practical experience, he says: “A few years ago both the Institution of Civil Engineers and the Institution of Structural Engineers removed the requirement to spend time on site before they became chartered.”

The rise of ‘global design offices’ can also have an impact, says Crick. “We frequently see the offshoring of design tasks,” he explains. “Many big projects will send basic tasks to offices in other parts of the world to complete.”

Using 3D models, and 4D models that show virtually how a building or structure is built, is already proving hugely helpful in explaining the realities and practicalities of the construction process, says Crick: “Designers can review what they intend to build and how to build it before they get to site. Things can be ironed out in the model.”

The idea of the Construction Risk Library, he adds, is to provide useful information at the point of need. And, by anonymising data, it should be possible for large organisations and projects to contribute information and experience that can benefit smaller companies with less resource or relevant experience.

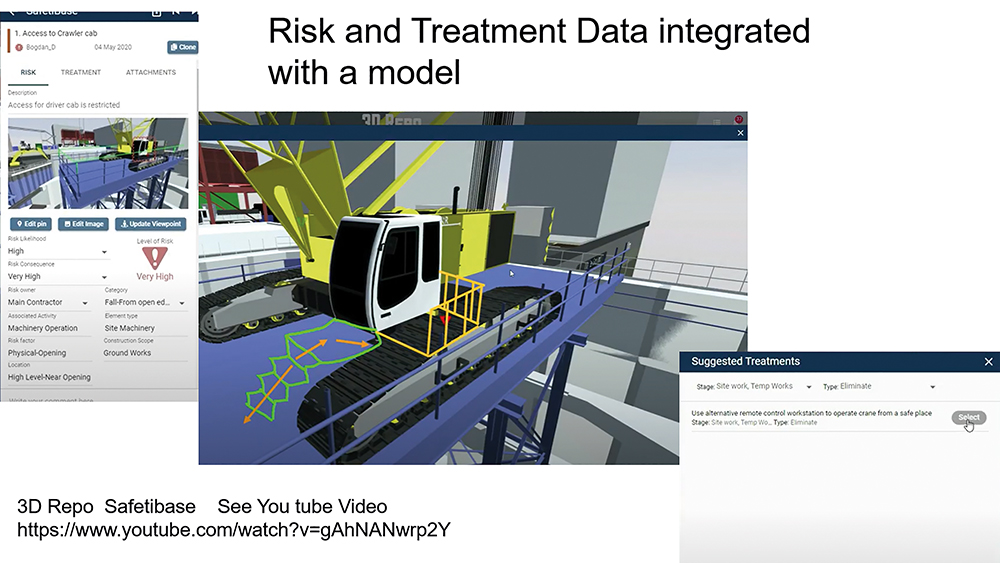

To prove that the idea of the library worked, the HSE elected to work with a tool called SafetiBase, created by software firm 3D Repo with industry partners including Atkins, Mott MacDonald, Laing O’Rourke, Costain, Bentley, HS2 and Tideway. The development of SafetiBase was funded by i3p and Innovate UK and conforms to PAS 1192-6:2018: Specification for collaborative sharing and use of structured Health and Safety information using BIM.

SafetiBase allows users to mark up risks within a model, complete various information fields and then apply a risk rating, which can be updated if changes are made. Although SafetiBase can be used in conjunction with 3D Repo’s BIM model viewer, it uses a common schema which means that it can be used as a SharePoint database with any BIM model.

“At the moment, at the procurement stages, the main data used is lost time injury rates. But that can be misleading. There are better ways to measure perform.”

“3D Repo make a lightweight version of SafetiBase available to anyone,” says Crick. “So, if any health and safety practitioners out there are interested and want to make use of it, they can.”

To date, the Construction Risk Library has been deployed on pilot projects with AstraZeneca (see below), Atkins, Faithful+Gould, Heathrow and Multiplex. One of the big challenges has been structuring the data, classifying it so that it can be correctly linked to both elements and activities in a build.

The tool isn’t quite at the stage where it alerts people of potential danger spots, though. 3D Repo is used to review designs at set stages, importing data from Revit or other software design packages. “You can view a BIM model, fly around it, click on it and add a warning triangle. They can then look at a data set connected to it which has been created by risk library projects,” explains Crick. “But it relies on the designer to have the foresight to understand that, at a certain point, risk can ensue.”

The plan is to get more companies and projects involved. Crick suggests that APS members could make a valuable contribution to the programme. More information on the Discovering Safety website: www.discoveringsafety.com.

Linking up to add value

Many of the Discovering Safety programmes are interlinked. Advances in one will fuel advances in others. For instance, the text mining tool, once honed, could potentially contribute data from a huge number of sources to feed into the Construction Risk Library. Other linked projects are looking at how to anonymise data, defining leading indicators for projects once on site and investigating how images can be analysed to spot risks.

The leading indicators project aims to investigate how historic safety and accident data from projects can be used to flag up potential risks on future projects. Currently health and safety programmes tend to be reactive, for instance introducing toolbox talks about slips and trips if incidents in that category have risen.

The problem with trying to look at historic safety data is that everyone does it differently, says Naylor. “There is no common agreement on how best to measure health and safety performance,” he says. “Different contractors use different KPIs.”

If there was a framework for collecting the right sort of data, it would be possible to train machine-learning tools to look at data and predict outcomes. HSE has been working with a group of contractors to find out what data is currently collected and where the gaps might be. One gap that’s already become apparent, says Naylor, is that there is not enough root cause information collected following on from accidents or incidents.

Consultancy Wood Group, which works in the oil and gas sector, is helping with the development of tools which could use data to help assign a risk score to a project at a certain point. This could help contractors to target efforts across projects, but also potentially be used to assess contractors’ performance at tender stage, says Naylor: “At the moment, at the procurement stages, the main data used is lost time injury rates. But that can be misleading. There are better ways to measure performance.”

Death of the PD?

With the promise of this wealth of safety risk data at a designer’s fingertips, APS members may fear that the role of the professional safety expert during the design phase may diminish or even disappear.

Crick allays these fears. “There is always going to be the need for specialist health and safety knowledge in construction,” he says. “It’s a case of when you apply that need. We would like to see APS members working with the clients more, right at the early stages of a project so that the clients understand the impact that their decisions are making on safety.”

AstraZeneca deploys Construction Risk Library

AstraZeneca was constructing an extension to the archive and quality assurance building at its Macclesfield campus – part of a programme of works that involves between 60 and 100 specialist construction projects. It is standard practice for the company to draw up detailed risk data and to update it throughout a project.

As part of the Discovering Safety pilot for the Construction Risk Library (see main text), AstraZeneca used the 3D Repo’s BIM model visualisation tool and SafetiBase, marking up potential risks on the 3D model and listing out the connected information. Through this, the team made early changes to reduce risks.

The most significant change was moving the plant required to control the climate with the chambers that will be used for storing. “It encouraged us to question whether we needed to put the plant on the roof. The answer was no and instead we installed it on the ground floor,” says AstraZeneca construction lead David Ayres.

Another detail was spotted by the building users. 3D Repo allows users to view a BIM model through an internet browser, a cheaper option than each user needing the design software, making it more accessible. “With the help of the 3D model, our client immediately spotted that the storage racking was too high. It was only by looking at the designs in 3D that our client was able to see this so early on,” says Ayres. “Without SafetiBase, we would have found out much later on in the process which would have cost time and money.”

Although it took time to feed its risk register information into SafetiBase for this project, that information is now there for AstraZeneca to use on the next one – which it intends to do, according to Ayres.