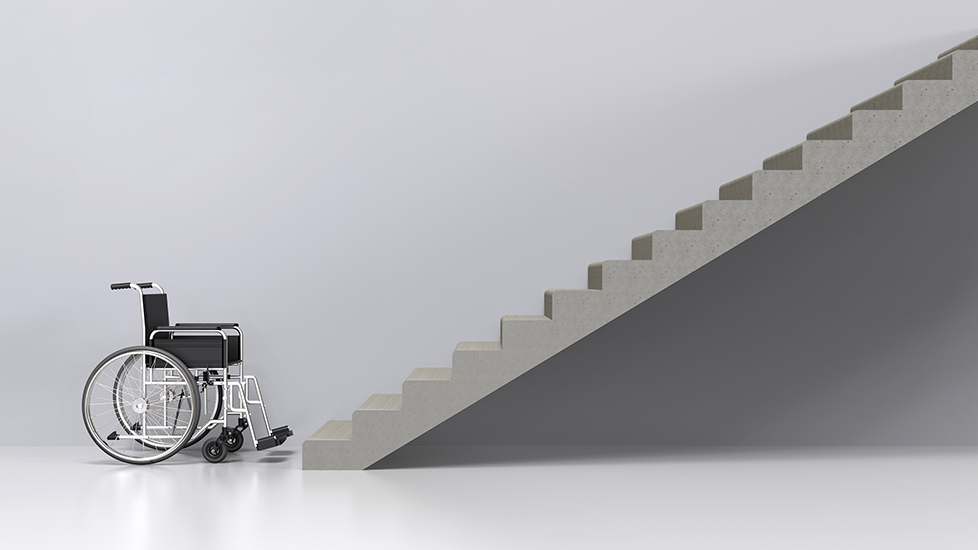

The government’s new National Disability Strategy sets out some immediate commitments aimed to improve disabled people’s lives. What changes can we expect?

The incident at the start of COP26, when Karine Elharrar, the Israeli minister for national infrastructure, energy and water, could not get into the conference centre in Glasgow in her wheelchair, was a stark reminder of the challenges faced by many people with disabilities when they are simply trying to go about their daily lives. Despite the Disability Discrimination Act of 1995 and the Equality Act of 2010, there is still a long way to go.

There were hopes that the government’s new National Disability Strategy, published at the end of July 2021 with little interest from the mainstream press, might start to address some of the remaining inequalities. The contents look promising. Part 1 pledges “immediate commitments” including sections on accessibility, transport and employment – all topics that could have knock-on impacts for those working in the built environment.

Adapting housing

One of the shocking statistics referenced in the National Disability Strategy is that 47% of respondents to the UK Disability Survey reported “some difficulty” in getting in and out of their homes. And while one in five people in the UK are disabled, just 9% of housing in England has “accessible features”, according to the English Housing Survey.

The strategy promises some action to address these problems. The government has committed that 10% of the 180,000 homes built through the £11.5bn Affordable Homes Programme between 2021 and 2026 will be for supported housing.

APS president Jonathan Moulam is not impressed: “That’s a woefully small number of properties, considering the need.” Moulam knows first hand how difficult it is to find adequate housing. His daughter, Paralympian Beth Moulam, uses a powered wheelchair and had to have a home specially designed and built just to be able to move around it.

“Managers need specific training that is relevant to people’s needs. Colleagues and line managers need to understand how people work best so that they are able to contribute fully.”

David Morgan, who heads up Wates Group’s disability working group, is more upbeat. “The strategy is positive both in terms of investing in housing and making sure housing is appropriate for people with disabilities,” he says. Morgan is managing director of the group’s property services division, maintaining a huge number of properties for social housing landlords.

For Morgan, the biggest challenge the UK faces is adapting our existing housing stock. One of the things he will be talking to his customers about is how to make the most of the grants that are available, such as the £573m Disabled Facilities Grant for this year.

“I suspect most customers, in the private and public sectors, are not aware of it,” says Morgan. “There are big government commitments and there is money available. How do we draw down that money?”

Employer commitments

One change that many hoped to see in the government’s new strategy was a mandatory requirement for larger companies to record and report information on disability. Currently there is a voluntary reporting framework for organisations of over 250 people. However, rather than mandating reporting, the strategy says that the government will consult on disability reporting for large employers.

Without some sort of stick, employers don’t appear to see the value in employing people with disabilities, despite declaring their commitment to diversity and inclusion. Although the percentage of disabled people with a degree has risen from 15.9% in 2013 to 23% in 2020, the employment gap has stayed the same, with the employment rate for working age disabled people 28 percentage points lower than for non-disabled people.

Some companies are reporting on disability without the mandate, in a bid to attract more people. Wates decided in 2019 that it would record the percentage of its workforce that declared disabilities, which was 0.9% back then. It also set itself a target: to have 3% of people with disabilities by 2025.

Wates has already exceeded its 3% target, says Morgan, who explains that people who weren’t previously comfortable about declaring a disability now feel able to do so. “The first big learning that came out of the disability working group is that people have physical and non-physical disabilities,” he says. “Often disabilities are neurological – for example autism, ADHD and dyslexia.”

Another lesson that came out of the working group was that targeted rather than general training is needed. “Managers need specific training that is relevant to people’s needs,” says Morgan. “Colleagues and line managers need to understand how people work best so that they are able to contribute fully.”

Next steps for Wates will be working out how to attract more people with disabilities. The Covid-19 pandemic has helped with that to some extent, he says, because it has demonstrated what can be done with flexible working arrangements.

As well as offering a range of working options, Wates will also be looking for ways to make people with disabilities more visible, says Morgan, to signal to other people with disabilities that this is an employer who wants them.

“It’s about being sufficiently comfortable bringing your whole self to work,” he says. “If you are deaf, dyslexic or have cerebral palsy we don’t want you to feel like it is a barrier to having a fulfilling career at Wates.”

Not far enough

Moulam, like many commentators, is disappointed by the lack of commitment to real action in the government’s strategy.

“There’s no meat. A lot of it is rhetoric and buzzwords,” he says, pointing out that the devolved governments are doing better than the Westminster one. “We have Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales quite clearly building their strategy around the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, yet this strategy quite clearly does not do that.”

While office developers have made great strides in considering accessibility and disability, housing is lagging behind, says Moulam. “A lot of things that help disabled people help everybody else too,” he says. “There’s a whole raft of things we should be looking at when we look at design.”

Being responsible for design to meet a commitment to diversity and inclusion should mean more than doing the bare minimum, he suggests. “It takes a step change in attitude from doing as little as you can get away with to having a social conscience.”