Improving safety in the industry requires more than regulation. It requires moral leadership and a willingness to challenge unethical behaviour at every turn, says Paul Nash.

Like many people in our industry, I have spent the last five years trying to make sense of the events that combined to claim the lives of 72 people in the fire at Grenfell Tower on 14 June 2017, an event made all the more tragic because it was entirely avoidable.

Had those with the power to act in the face of mounting evidence of the risks of combustible cladding done so earlier, and had those corporates with an interest in promoting these products not put profit before human lives, the outcome of an electrical appliance catching fire in a high-rise building would not have led to the loss of so many lives.

Since the fire, much of the focus has been on the failure to properly regulate the industry linked to the government’s stated policy to reduce the amount of regulation. This regulation reduction is a policy that appears to have been pursued in ignorance of the implications and the potential consequences for those who most needed the protection it provided.

The need for better regulation and enforcement was one of the key recommendations of Building a Safer Future, the final report of the Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety led by Dame Judith Hackitt.

This has led to the creation of a new regulator for building safety and the introduction of legislation in the form of the Building Safety Act 2022. The Act sets out a new regime for higher-risk buildings aimed at ensuring the safety of those in and around them.

But regulations and standards are only effective if there is a culture of compliance that puts the safety and wellbeing of those who use the buildings that we create before profit or politics.

This requires moral leadership and a willingness to challenge unethical behaviour at every turn, to make a conscious decision to eschew what Dame Judith Hackitt described in her report as the “race to the bottom”.

Taking this leadership stance isn’t a guarantee that mistakes won’t be made. No system is perfect. People sometimes get things wrong. But it can create a culture where it is acceptable to challenge and not feel afraid to do so.

Learning from failure

Which leads me to Gene Kranz, one of my personal heroes. Kranz was the flight director for the Apollo programme in the 1960s and oversaw the mission to put a man on the moon.

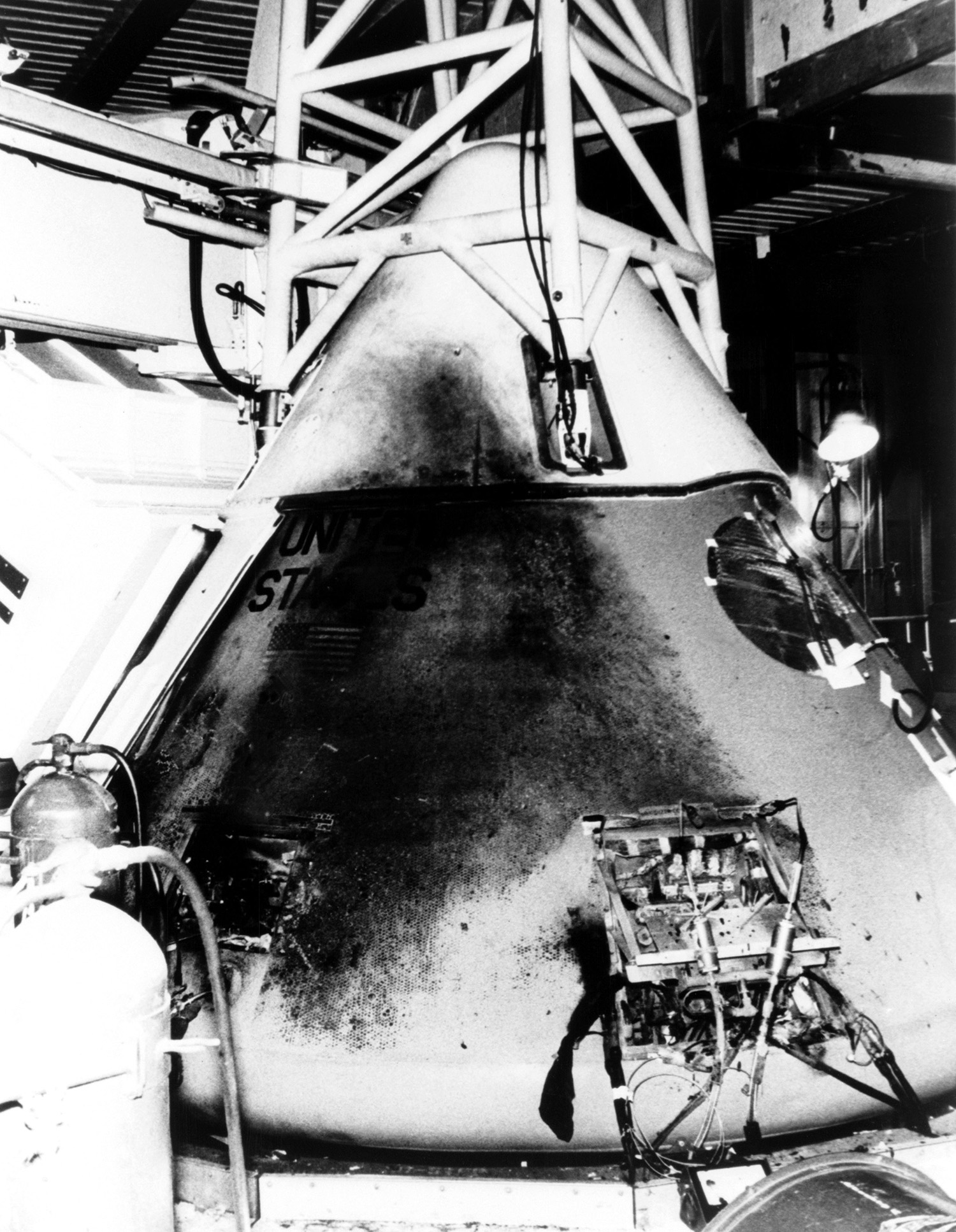

On 27 January 1967, a fire on the launchpad at Cape Kennedy, Florida, claimed the lives of three astronauts: Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee. They were conducting a countdown simulation ahead of what would have been the first piloted Apollo flight.

It was a tragedy which, like Grenfell, could have been avoided. But it was what Kranz did in the immediate aftermath of the fire that was important. He gathered his team together and addressed them in what became known as the Kranz Dictum, and he began by spelling out what had gone wrong.

“Somewhere, somehow, we screwed up […], not one of us stood up and said: ‘Dammit, stop!’”

He then went on to spell out what needed to change.

“From this day forward… we will never again compromise our responsibilities… we will never take anything for granted… we will never be found short in our knowledge and in our skills.”

I have reproduced the Kranz Dictum in full in this article (see box below) because it should speak to anyone in our industry who is looking to express, in words, the type of behaviours that define what it means to be competent.

There is a lot that has, and will, be written about the Grenfell tragedy. In his excellent book, Show Me the Bodies: How We Let Grenfell Happen, Peter Apps describes much of what is known about the events that led to the fire and the night of the fire itself. But it also reminds us of the human consequences and how the events of that night continue to affect the lives of so many people.

When the final report of the independent public inquiry is published later this year, I expect the focus to shift to how those responsible are to be held to account. Those who lost loved ones in the fire at Grenfell Tower need and have a right to justice.

But that should not distract from the responsibility that we all have in this industry to act now to ensure there is never another Grenfell Tower fire.

And that means being prepared, when necessary, to say, “Dammit, stop!” and, importantly, know that we will be listened to.

Paul Nash is past president of CIOB and sits on the Industry Safety Steering Group. Chaired by Dame Judith Hackitt, it reports on the progress of construction in delivering culture change and holds the industry to account on behalf of the government.

The Kranz Dictum: Tough and competent

How the NASA flight director defined accountability after the Apollo 1 fire.

Spaceflight will never tolerate carelessness, incapacity and neglect. Somewhere, somehow, we screwed up. It could have been in design, build or test. Whatever it was, we should have caught it. We were too gung-ho about the schedule, and we locked out all of the problems we saw each day in our work. Every element of the programme was in trouble and so were we. The simulators were not working, Mission Control was behind in virtually every area and the flight and test procedures changed daily. Nothing we did had any shelf life. Not one of us stood up and said, “Dammit, stop!”

I don’t know what Thompson’s committee [set up to investigate the incident] will find as the cause, but I know what I find. We are the cause! We were not ready! We did not do our job. We were rolling the dice, hoping that things would come together by launch day, when in our hearts we knew it would take a miracle. We were pushing the schedule and betting that the Cape would slip before we did.

From this day forward, Flight Control will be known by two words: “Tough” and “Competent”. Tough means we are forever accountable for what we do or what we fail to do. We will never again compromise our responsibilities. Every time we walk into Mission Control, we will know what we stand for. Competent means we will never take anything for granted. We will never be found short in our knowledge and in our skills. Mission Control will be perfect.

When you leave this meeting today you will go to your office and the first thing you will do there is to write “Tough and Competent” on your blackboards.

It will never be erased. Each day when you enter the room these words will remind you of the price paid by Grissom, White and Chaffee. These words are the price of admission to the ranks of Mission Control.