Averaged over the year, two construction workers take their own life every working day. Andrew Pring reports on a new initiative that unites contractors, clients and charities.

Towards the end of January, a high-level industry meeting was convened to find new solutions for tackling the construction sector’s worryingly bad mental health record.

Leading the virtual meeting was Bill Hill, chief executive of the Lighthouse Club, who was to unveil a new mental health campaign called Make It Visible. Tuning in to hear what he had to say about the new initiative was a broad spectrum of clients from both the private and public sectors, including the then Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS), as well as contractors and mental health charities.

Also represented was the Construction Leadership Council, which has challenged Hill to unite the industry and work collectively to improve the wellbeing and welfare of construction’s workforce “for this generation and the next”.

Speaking with Project Safety Journal in advance of the meeting, Hill explained why the event was so vital and why so much rested on it.

“One of the big problems to date is the sector’s lack of a unified approach to mental health. There should be a proper benchmark for everyone to index and measure their progress against. We want the whole industry to unite behind one single wellbeing programme and we believe the Make It Visible campaign can achieve that. I’m more optimistic about the year ahead and what we can achieve than I’ve ever been before.”

Courses of action

Alongside Hill at the meeting was Professor Billy Hare, whose research covers safety, health and wellbeing in construction and who lectures on construction management at Glasgow Caledonian University. He has been studying mental health issues for the Lighthouse Club since the Stevenson-Farmer review of mental health in construction in 2017.

Setting out Hare’s analysis of recent studies into the industry’s approach to mental health over the past two years, Hill and his team suggested various courses of action. He then asked the industry attendees to decide priorities and set up teams to deliver a deep and lasting step change in a concerted pan-industry way.

Helping promote whatever plans were hatched at the meeting will be the Make It Visible campaign’s Ford Transit vans. These are decked out in an eye-catchingly colourful livery, donated free of charge by Ford, as is access to Ford’s global marketing agency.

“The sector needs to address the root causes of poor mental health, which are so often linked to construction’s adversarial nature and macho culture.”

A pilot scheme last year saw trained mental health workers visit 150 sites around the country in one of these luminous vans. The workers talked with over 7,500 operatives about the many industry initiatives open to anyone suffering from stress and anxiety. Tellingly, says Hill, 95% of construction workers were totally unaware of a single one of those initiatives.

Suicide in construction rising

Suicide numbers are just one indication that the Make It Visible campaign has a very big job on its hands. Another is that surveys show the depth of misery in the construction sector far outstrips that of almost every other occupation.

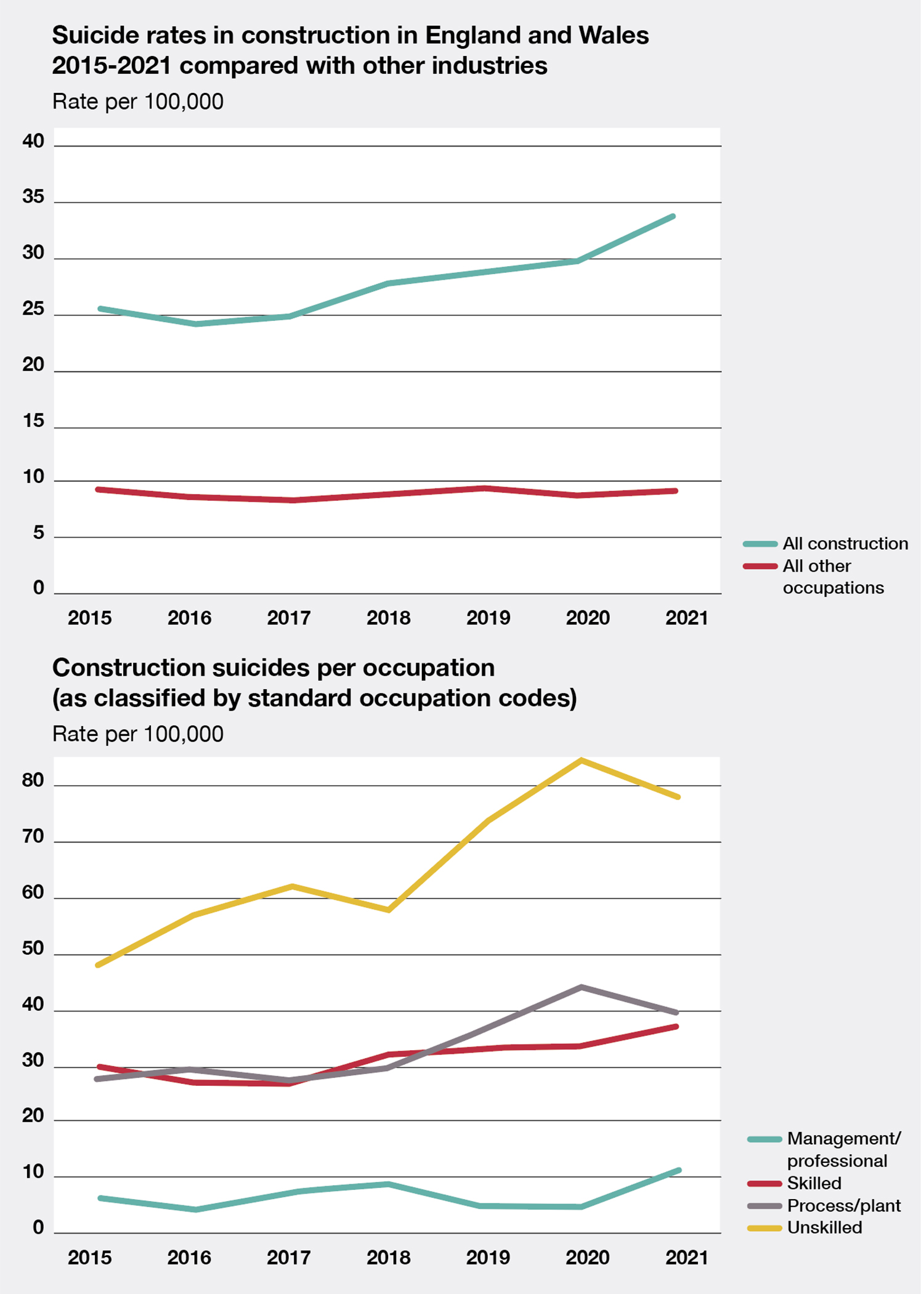

To take the starkest statistic of all, 34 construction workers per 100,000 took their lives in 2020-21, compared to nine per 100,000 in all occupations – nearly four times the national average. (The ONS states 10.5 per 100,000, but this includes the construction sector: Professor Hare has arrived at the ‘nine’ figure after excluding construction.)

This equates to two construction workers taking their own life every single working day, or 507 for the year (the ONS only covers England and Wales; Scotland does not break down the number of suicides in its construction sector).

And, to the consternation of all and in contrast to a recent slight decline in whole-nation suicide rates, the situation has been getting worse over the past few years. In 2015, nine fewer construction workers per 100,000 (25 in total) died by suicide, evidencing a rise in construction suicides of 26% in the past six or so years.

The vast majority of construction suicides occur among site operatives, but white-collar workers are by no means immune. ONS figures show that construction’s management and professional occupations have had the lowest rates of death by suicide since 2015 and had been on a downward trajectory. However, in 2021 the rate for this group more than doubled from 4.9 to 11.2 deaths per 100,000 – the highest since the data was recorded from 2015.

The 2021 rate for skilled workers increased 21% on the previous five-year average, while plant and process and unskilled workers rose 18% and 16% respectively, although the rate for each of these occupations did actually fall slightly from the previous year.

Unforgiving working environment

Suicide is, of course, not the only indicator of the deep well of despair in the construction sector. In a survey by the Chartered Institute of Building in 2020, 26% of construction professionals said they had considered taking their own life in the previous 12 months.

Why construction workers suffer such high levels of poor mental health is no mystery. It’s a tough, unforgiving working environment, where huge pressures can build up when trying to bring projects in on time and budget. Long hours, physically demanding and often dangerous activities, an itinerant lifestyle that may mean many nights away from home and loved ones, with the additional worry of not knowing where the next job is coming from, all add to the toxic mix.

So does construction’s traditionally ‘macho’ culture, which can act as a strong barrier to sharing feelings of unhappiness and stress and reaching out for help. The overwhelmingly male nature of the industry (87% of workers) also affects the suicide rate, as men have a far higher propensity to take their own life – of the 6,000 suicides last year in the UK, 5,000 were men.

Financial pressures play their part too, particularly for the SME section of the industry, where cash flow can often dry up and finances buckle. Fifty-three per cent of the sector consists of individual self-employed workers, often on zero-hours contracts with no paid sick leave.

With all the economic stresses caused by both austerity and increasing interest rates, many more workers have been finding it harder to make ends meet. Covid and its effect on the ability to work may also have played a part, though industry experts differ over the extent.

Self-employed pressures

Mates in Mind, a mental health charity dedicated to helping those in the construction industry, carried out in December 2021 a major study of the mental health of self-employed construction workers and those working in small firms. It showed that intense workloads, financial problems, poor work-life balance and pressures on the supply of materials were combining significantly to raise stress and anxiety levels.

“What we’re aiming to do is normalise the conversation around mental health.”

Overall, almost a third of respondents had ‘severe’ anxiety, with a further third in the ‘moderate’ anxiety category and the remainder in the ‘mild’ anxiety group.

Almost half of respondents reported that they found “talking about my mental health extremely difficult” and almost 70% agreed that “that there is a stigma about mental health which stops people from talking about it”. Respondents with ‘severe’ anxiety – more than those with less severe anxiety – reported significantly lower willingness both to seek help and provide it to others.

Mates in Mind pinpointed five areas which respondents reported were contributing relatively frequently to feelings of stress, anxiety or low mood. These were: workload that is too high (42% experiencing this frequently); difficulties with business partners/colleagues (37%); pressure at work (35%); anxiety about family or relationship problems (33%); and financial problems (32%).

Mental health initiatives

These stress factors are, of course, well understood throughout the industry, and it’s important to acknowledge that enormous efforts have been made over the past decade and more to address them. Many main contractors have admirable mental health programmes – both reactive, seeking to help employees and supply chain members when problems strike, and proactive, teaching managers and teams to create a supportive working climate that encourages good mental health.

BAM is one of the leaders in developing a progressive, universal approach to the problem for both its staff and supply chain. Its work has been recognised through a number of major mental health awards.

Over the past few years Ruth Pott, head of workplace health and wellbeing for BAM UK & Ireland, has driven a comprehensive programme of measures aimed at improving mental health at work. She has had the full support of the main board. Most managers are trained in mental health awareness and, out of a directly employed staff of 6,500, over 400 have been trained to become mental health first-aiders and act as wellbeing champions, playing an active role in spreading the message that “it’s okay not to be okay”.

Such is the scope and universality of BAM’s wellbeing programme, there are too many measures to list here – but one of the most successful has been onsite ‘wellbeing rooms’ which offer safe spaces for anyone on larger sites to have confidential conversations with a wellbeing champion. Another is 24-hour access to an employment assistance programme run by a specialist external company.

“It’s all about awareness training and taking a more proactive approach,” says Pott who, in 2021, was named ‘Most Inspiring Mental Health Leader’ by the national mental health organisation This Can Happen. “What we’re aiming to do is normalise the conversation around mental health. Life is hugely challenging and sadness is quite normal. People have to learn to live with anxiety, but we can support them and help them cope.”

Taking a proactive approach

BAM also makes a link between physical and mental health, and the impacts of poor mental health and wellbeing upon safety. The firm encourages participation in healthy activities and habits as part of its efforts to drive wellbeing.

Skanska is another company that’s been showing the way towards better mental health since it embarked on its own wellbeing journey in 2016. Nearly 60% of its 3,300 UK staff have been through mental health awareness training and it has a network of 165 mental health ambassadors, trained by Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) England. Like BAM, it has an externally run employment assistance programme which offers round-the-clock support and counselling.

At Willmott Dixon, a similarly comprehensive mental health support package is in place, even down to offering safe places where their Ukrainian workers can phone loved ones at home.

Mark French, head of health, safety and the environment, runs the company’s All Safe Minds campaign, which aims to ensure vulnerable workers are able to tap into a variety of recognised resources as quickly, easily and privately as possible. All Safe Minds encourages everyone to watch out for anyone who might be struggling with pressures and to start a conversation. 15% of Willmott Dixon’s staff are trained as mental health first-aiders.

French says the company has recently switched to a mental health app run by the Lighthouse Club, and it’s proving effective. “We’ve employed the Thrive app for several years but it uses language with which office workers are comfortable, but which does not necessarily work for site workers. The Lighthouse Club’s app is more attuned to their way of speaking.

“It’s part of the work we’re doing on sites to ‘make it real’ and we’re also trying to identify workers who are not necessarily supply chain managers but are characters that people look up to and who command respect. They

can be very good at encouraging people to speak up and make use of our support systems. And they can help us keep banging the drum and getting the message out there.”

What needs to change?

The authors of the hard-hitting report Thriving at Work: The Stevenson/Farmer review of mental health and employers in 2017 would undoubtedly be impressed by how wholeheartedly the industry has moved to embrace and implement their recommendations.

Yet, for all the many impressive initiatives in place, it’s clear they have failed to bring down the rates of depression and suicide across the sector. Why? And what will make the difference? Is it a question of continuing to do what’s been done over the past five or so years and taking the mental health message further and further down the supply chain? Or could there be a more fundamental problem – one to do with the systemic nature of the construction industry itself – which prevents real progress being made?

“We want the whole industry to unite behind one single wellbeing programme, and we believe the Make It Visible campaign can achieve that.”

Dr Nick Bell, a former risk consultant in the built environment, a chartered psychologist and currently a part-time principal lecturer at Cardiff Metropolitan University, has taken a professional interest in wellbeing for a number of years and has studied the construction industry closely. He’s convinced that the “strongly adversarial” and “contractual and confrontational” culture, highlighted in the Egan report of 1998, is still prevalent and at the heart of the industry’s mental health problems.

“Projects often have unrealistic timetables and financial conditions. This leads to people blaming each other and this conflict gets pushed down the line, putting tremendous pressure on the small trades.

“We need to get away from clients taking the cheapest bid and contractors working at unrealistically low cost levels with all the onsite stress that can cause.

“Clients need to set projects off on the right foot with an effective set-up. They need to involve the contractor as soon as possible, helping get the design right and ensuring early and effective co-ordination between the trades. That way, the building is much safer to build and people can develop much more positive relationships on site, which means less stress all round.”

Psychological needs

Bell is also convinced not enough is being done to develop more harmonious relationships on site. “In the UK, we don’t pay enough attention to the psychological needs of our workers. Managers need to understand what makes people tick and how to make individuals feel respected and valued, part of a team and feel a sense of purpose in their work. It doesn’t need to be complicated – you just need to train site managers and give them the time and motivation to implement this.

“At the moment, there’s still too much of a ‘them and us’ mentality between managers and workers. So the mental health first-aiders you can see on sites these days are really just sticking on plasters and not addressing the underlying problems. It’s no good having ‘work well Wednesday’ sessions if everyone’s too busy to attend.”

There are some signs of change, Bell notes. Since 2021, the Health in Construction Leadership group has been focusing attention on “proactively fostering positive mental health and wellbeing”, not just preventing ill health.

He points to the various guidance notes for construction clients. “If clients do what they need to do from a CDM perspective, we will have the foundations of a project in which people can perform at their best and thrive. If that’s followed through, then you can create the right culture on any project.”

Treating symptoms rather than causes

Professor Billy Hare, the Glasgow academic who works closely with the Lighthouse Club, shares Bell’s concern that initiatives are treating the symptoms rather than the causes of construction’s mental health crisis.

“Counselling and advisers are certainly needed for the short term, but the sector also needs to address the root causes of poor mental health, which are so often linked to construction’s adversarial nature and macho culture. In my opinion, there are common denominators to the mental health problem and they link to productivity, quality and conflict. Getting this issue right really is all to do with the way we procure our buildings.”

No doubt many attending January’s Lighthouse Club meeting would be stung by these comments. They and others could quite justifiably say that this is exactly what they are already doing and that they could not be more passionate about improving construction’s mental health record.

But it’s clear that much more still needs to be done. Given the Construction Leadership Council is calling for a concerted approach to improve the wellbeing of construction’s workforce “for this generation and the next”, industry leaders seem to have recognised that too.

Whatever plans emerged from the Lighthouse’s virtual meeting, Bill Hill’s optimism for the year ahead rests on the whole industry getting behind the charity and co-ordinating mental welfare activities.

Time alone will tell if it will work. But, in Hill’s opinion, the sector’s reputation is well and truly on the line: “To encourage the next generation to see construction as a top career choice,” he says, “the industry must unite to turn this moment into a long-term movement to drive cultural change.”