Musculoskeletal disorders are one of the main causes of ill health in construction, affecting over 37,000 workers. Could innovative approaches to risk management or emerging tech like wearables, exoskeletons and computer vision make a difference? Stephen Cousins reports.

Despite decades of research and development and the redesign of construction work and building sites, musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) continue to plague the sector, accounting for the majority of workplace injuries.

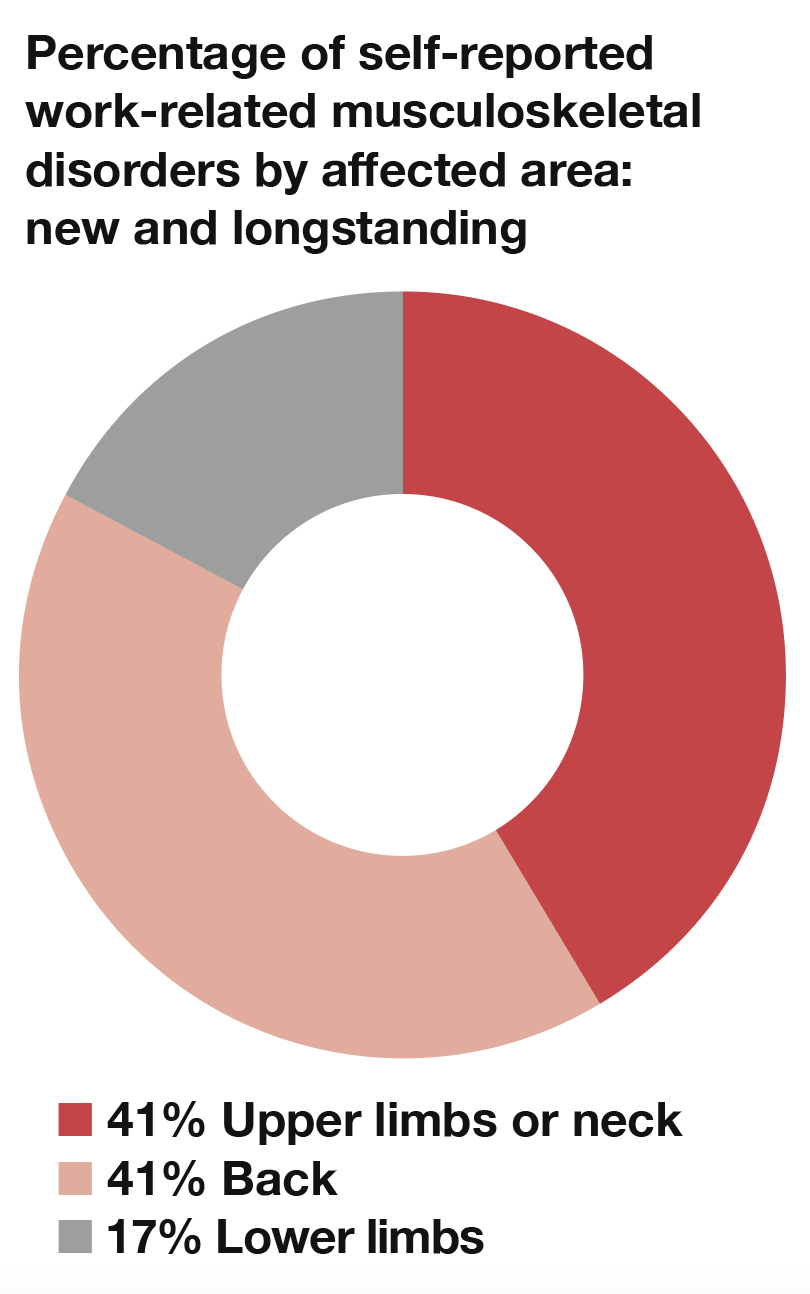

An average of 37,000 workers had a new or longstanding work-related MSD between 2020/21 and 2022/23, according to HSE figures, equivalent to 54% of all ill health in construction.

Triggered by damage or injury to tissue or joints in the upper or lower limbs and back, MSDs are a source of chronic or acute pain that impacts workers’ ability to perform tasks safely and efficiently. This can stunt careers and affect quality of life outside work.

Keen to identify viable solutions, researchers and safety professionals are trying new approaches to MSD risk management. Contractors are turning to emerging technologies – including wearables, computer vision, data analysis tools and exoskeletons – in a bid to eliminate or minimise worker exposure, often with positive results.

However, if cutting-edge systems are going to transform health and wellbeing at scale, experts also warn that means addressing barriers around the cost of investment in an industry operating on low margins, workplace culture and resistance to innovation.

Seb Corby, principal consultant at Safetytech Accelerator, a technology accelerator focusing on safety-critical industries, says: “One of the biggest drivers is regulation. It’s also large clients like National Highways, HS2 and Network Rail, asset owners and managers who employ large numbers of people. Change won’t come until they stipulate that tier 1 contractors need to be using certain pieces of PPE or low-hand arm vibration equipment etc. We need that external pressure.”

Root causes

Despite the widespread impact of MSDs, identifying their root causes remains difficult. HSE research into the construction, healthcare and transportation and storage industries, from 2018, found that employers were typically unable to determine if MSDs were caused on the job, through daily tasks such as bending, awkward positions or lifting, or as a result of natural ageing and lifestyle choices.

Back pain was the MSD employers encountered most often, but many lacked detailed data to back this up.

Employers and workers in all three sectors had “fatalistic attitudes” towards MSDs, said HSE, believing they had little control over their occurrence. Employers were generally confident they were doing everything possible to tackle them via existing preventative and managerial approaches.

In addition, MSD-related injuries were often thought of as singular events requiring immediate action, in line with existing workplace health and safety policies, rather than cases with a gradual or cumulative onset that require other interventions.

Other research by Loughborough University, from 2020, found that construction employers were underestimating rates of MSDs and the impact on a worker’s safety and productivity. It uncovered growing evidence of MSD presenteeism, with workers remaining at work despite pain, which researchers said might be more costly than absence because of the need for workplace interventions.

Addressing hazards at the design stage is the first line of defence when trying to eliminate or minimise manual handling risks. Designers and pre‐construction planners are required to consider them under CDM regulations, but again evidence suggests more could be done.

Loughborough University concluded that risk assessments at all stages were too generic, and recommended pre‐work risk assessments should include not only hazards but people, taking into account individuals’ capabilities.

Improving risk assessments during planning and scheduling could, it said, create an opportunity for those suffering MSD-related pain or injuries to state what tasks they are comfortable with, and identify options for job rotation or ‘tweaks’ to jobs over the course of a day.

According to Lee Marsden, managing director of Majestic Site Management, the new change control process introduced under the Building Safety Act could help reduce worker exposure to MSD-related injuries by preventing the easy substitution of products and components.

Under the legislation, applying to all higher-risk buildings over 18m tall, the client must apply to the Building Safety Regulator (BSR) to make any ‘major’ or ‘notifiable’ changes to detailed design after a project has passed Gateway 2 and been signed off by the regulator.

“Where, before, the contractor might have tried to save money and go for a heavier material rather than a light material, or buy large sheets that workers need to cut on site, rather than smaller, manageable sheets, now they can’t do it because it effectively has to go through the approvals process again,” says Marsden, who adds that hopefully the same approach will filter down to smaller jobs too.

Tech interventions

Improved guidance and regulation is important, but the pervasive nature of MSDs has led some companies to look to cutting-edge innovations like computer vision, wearable sensors, exoskeletons and extended reality to monitor and prevent MSD-related physical strain on workers, and improve ergonomics.

Some of the best examples of tech-enabled MSD prevention for construction were identified by the UK’s Safetytech Accelerator in collaboration with the National Safety Council – the American equivalent to the HSE – at two recent Safety Innovation Challenge events in the US. The challenges took place in 2022 and 2023 and covered innovations designed to tackle manual material handling MSDs and upper body MSDs.

Finalists included a bionic glove designed to reduce hand injuries by enabling workers to use less grip force on repetitive tasks.

The Ironhand was developed by Bioservo on sites run by French contractor Eiffage. It features pressure-sensitive sensors in the fingertips and artificial tendons that run down the sides of fingers connected to motors in a backpack. When workers grab an object, such as a rebar tray or a shovel, the glove provides a boost to grip, helping alleviate hand strain and pressure on the wrists.

Eiffage’s tests on operatives, including fitters and welders, measured reductions in effort ranging from 25 to 80% depending on the task. The contractor said the system should help reduce occupational injuries.

Nadia Echchihab, head of innovation programmes at Safetytech Accelerator, tells PSJ: “The technology helps workers continue to work for longer without feeling fatigue, reducing exposure to MSDs… When you get older, your grip is not as strong as previously, so it means an older person could continue doing the task with the same strength as a younger one.”

Other finalists included TuMeke Ergonomics, whose computer vision technology scans construction workers’ movements during manual material handling activities to better identify MSD risks and assess targeted solutions.

UK-based Reactec’s R-Link smart watch informs the wearer of exposure to hand-arm vibration (HAV) by displaying HSE HAV risk assessment exposure points in real time.

According to Echchihab, the watch satisfied judges’ requirements for technologies that could be cheap to deploy and apply to multiple different tasks. “Getting a special wearable for each worker is not very sustainable if you have to buy lots. R-Link can be shared – different workers can use the same device in separate sessions, helping cut the cost,” she says.

Body bionics

One emerging MSD-prevention technology generating a buzz in construction is the exoskeleton, or exosuit. The blend of human intelligence and robotic strength has moved from concept to real-life deployments in various industries.

Exosuits aim to boost human performance and provide support for the back, legs, hands or other areas affected by prolonged strain that can trigger musculoskeletal disorders.

They can either be active, using machine components to drive physical movement, or passive, harnessing human movement, materials, springs and dampers to energise the system.

What is thought to be the first detailed empirical study of exoskeleton use in live construction was recently completed by Built Environment – Smarter Transformation (BE-ST, formerly the Construction Scotland Innovation Centre), the University of Strathclyde, and National Manufacturing Institute Scotland (NMIS).

Part of the EU’s Exskallerate programme, established to test the benefits of exosuits for European SMEs, the initiative was divided into two phases. The first saw construction businesses trial two passive exoskeletons, the Herowear Apex and Auxivo Liftsuit, both designed to protect the upper body and back, in controlled factory conditions for manufacturing and loading.

Subsequent ‘field lab’ tests saw workers from Kenoteq, Ecosystems Technologies and Indeglas wear the exosuits while carrying out typical roofing, plasterboarding and offsite assembly activities over several days at BE-ST’s facility in Blantyre, Scotland.

Researchers gathered qualitative data and feedback from six workers, four of whom had their movements captured using dimensional motion tracking cameras, to measure the effect of exosuits on motion when carrying out different tasks.

Analysis revealed that almost all recorded activities were affected in some way by the exosuits, whether reducing or increasing the users’ range of motion, changing their behaviour during bending and lifting or impacting productivity time.

Researchers concluded that the suits “went some way” to encourage safer postures, however this was highly dependent on the type of activity, the time spent in the suit, the suit type and the user. Some activities benefited from a productivity increase.

So could exoskeletons soon become a regular form of PPE, similar to hard hats? Alan Johnston, impact manager at BE-ST, says the answer is “possibly” but it will likely require another generation of suits before that.

“Construction is quite varied. Whether you’re a bricklayer, a window fitter or a roofer, there are lots of different factors to be considered and it’s hard at the moment to say there is a suit suitable for all of these,” he says.

Tough sell

The onsite trials revealed conflicting feedback from workers – while some said the suits were aiding lifting, or helping support their back, others said switching to different activities created a strain in another area of the body.

“Some became uncomfortable or hot, or said the straps were rubbing their shoulders. Some felt discomfort in the thigh, or on one in their hips,” says Johnston. Designs might need to evolve in future, he adds, to match suits to a particular task and individuals of different sizes and abilities, potentially by using adjustable straps.

According to Sam Chapman, managing director of brick manufacturer Kenoteq, workers doing manual handling, lifting and building walls thought they were “a positive step” and they were “less tired at the end of the day”. However, one worker who had to operate a forklift found them “really annoying” because moving into a seated position meant acting against the movement of the suit. “Although the principle of the exosuits was sound”, the benefits were not enough to justify investment at the current time, he added.

Some employers may be swayed to invest by the reported productivity gains – less tired employees should be able to work at a more consistent and efficient pace. However, the tech faces other barriers to uptake, for example, lacking certification demonstrating the health and wellbeing benefits to contractors or endorsement by the HSE as a recommended form of PPE.

Scaling up adoption of MSD innovations in general remains a difficult proposition given the conflicting priorities that still operate in construction. The HSE’s MSD research concluded that the industry had reached “a plateau in effective interventions” due to a lack of innovation, with “a stalemate” in place over who should take responsibility for making improvements.

Challenging contractual pressures, unhelpful workplace cultures and corner-cutting, including the use of incorrect equipment, remain commonplace. “When people are pricing for jobs, they need to factor in the cost of investment in systems to help with MSDs, but too often all the client sees is a bottom-line figure, so they go for the cheaper option,” says Marsden.

If employers can be convinced of the overall value proposition, also factoring in long-term benefits for health and wellbeing, things might change.

“A lot of technology still needs to be fully proven in terms of how it can be implemented into a workflow and create change,” says Corby at Safetytech Accelerator. “We’re at a point where we’re still proving the value and making sure technologies can be embedded well enough for people to want to take them up.

Exoskeleton suits trialled in air jack role

A major infrastructure project involving the “construction of train viaducts” in the UK has rolled out active exoskeleton suits to workers after successful trials of the technology.

According to exoskeleton supplier Stanley Handling, the exosuit was recommended to the client based on AI-powered video scanning diagnosis designed to match the right exoskeleton suit to an activity.

A specialist safety consultant visited the site and used the WearHealth technology to assess workers lifting 30kg air jacks from the floor onto one shoulder. The air jacks are used to attach large bolts onto metal splines that connect concrete sections of train viaduct.

Videos of workers performing the task were processed by an AI-driven algorithm to assess risk. An ergonomist then reviewed the data to take into consideration the weight carried, static movement and scheduled breaks.

The data informed a written report recommending the use of an active exoskeleton suit designed to decompress the spine. The exosuit was then trialled by the contractor using body-mounted sensors to verify its effectiveness. The improvement was verified and exoskeletons were rolled out to the entire team.

Andre Jutel, head of ergonomic safety technology at Stanley Handling, says: “Getting workers involved from the trial stage not only helps them experience the improvements that this type of technology makes to their day-to-day activities, they can also see the data generated, which helps them understand how they can best safeguard their health going forward.”